Maybe the question feels a bit intrusive or silly. But it does seem to be a “thing” these days. Just recently, students in Hamilton’s film club were asking a range of faculty to name their four favorite films.

I often fumble at a response to the question. For a decade or two, I’d offer one or another snide response: “Well, I guess that would be Larry Gottheim’s Fog Line!” Fog Line (1970) is an 11-minute, silent, single shot of fog gradually clearing over a small dell to reveal, part way through in the bottom third of the frame, two barely visible horses slowly grazing across a pasture.

In the last few years, I’ve come to respond with a question of my own: “My favorite film, for what?” Another snide, maybe pretentious, response, but at least one that suggests the many ways in which cinema can matter to us.

Certainly, judging from the fact that I paid to see it three times (and snuck into a fourth screening!), A Complete Unknown is a current favorite not only because I enjoyed revisiting Bob Dylan’s career — and seeing Timothée Chalamet’s remarkable performance — but also because the film feels like a mythic metaphor for a long-ago crucial change in my personal/professional life. It was also fun to be in a theater with so many moviegoers my age. Dylan’s long career has been one of the soundtracks of our lives. Indeed, his “Gotta Serve Somebody” helped me determine the focus of my life as a film scholar.

If I think about films that transformed my sense of what cinema can do, one favorite is the original King Kong (1933), which I experienced in its theatrical re-release in the early 1950s. My parents had suggested I go see it alone at a downtown theater, but told me nothing about it. At first, I was bored. Nothing much seemed to be happening as the ship sailed toward a tropical destination, though for some reason, the filmmakers who’d hired the ship were teaching Ann Darrow how to scream! Pretty weird.

Then the boat arrives at Skull Island; the natives steal Ann and take her through an immense gate in a giant wall to tie her to a sacrificial altar. The natives run back through the gate, leaving Ann alone. On top of the wall, a huge gong is struck — then TOTAL SILENCE. The gong is struck again. Suddenly, a strange noise! I’m half standing, ready to run out of the theater, barely suppressing the urge to yell, “Get out while there’s still time!” And then there’s Kong himself, giant on the big screen, tearing through the trees, releasing Ann from the altar, and carefully carrying her — and me! — into a new cinematic world.

I’ve been through many cine-transformative moments. Hating Fellini’s 8 1/2 when I saw it as an undergraduate in 1963, then loving it when I saw it as a graduate student a decade later, taught me I could learn to admire a film. Seeing Buster Keaton’s The General in 1970, when it had finally become available after decades in the dark, made clear that Keaton was and remains not just a funny comedian but one of the greatest American directors.

In 1972, I was appalled by my first program of “avant-garde” films, only to realize that, despite my fury, I’d just learned what film theory was. And, very recently, finding my way to Max Tohline’s video essay (2021) online transformed my sense of what media scholarship, including my own, could be.

The truth is that my actual favorite is not a film but the “meta-film” I construct when I teach Introduction to the History and Theory of Cinema. Last fall, the course included 103 films, each of them a favorite for my teaching — Chaplin’s The Kid, Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, Fritz Lang’s M, Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon, Hitchcock’s Psycho, Bob Fosse’s Cabaret, Bill Greaves’ Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone, Laura Poitras’ Citizenfour, Chloé Galibert-Laîné/Kevin B. Lee’s Reading // Binging // Benning, and yes, of course, Gottheim’s Fog Line.

My hope is that this slowly evolving meta-film is as revelatory for my students as it continues to be for me — an immersion in an art form so rich, so engaging, that we can never fully comprehend its ongoing transformations and its various ways of transforming us.

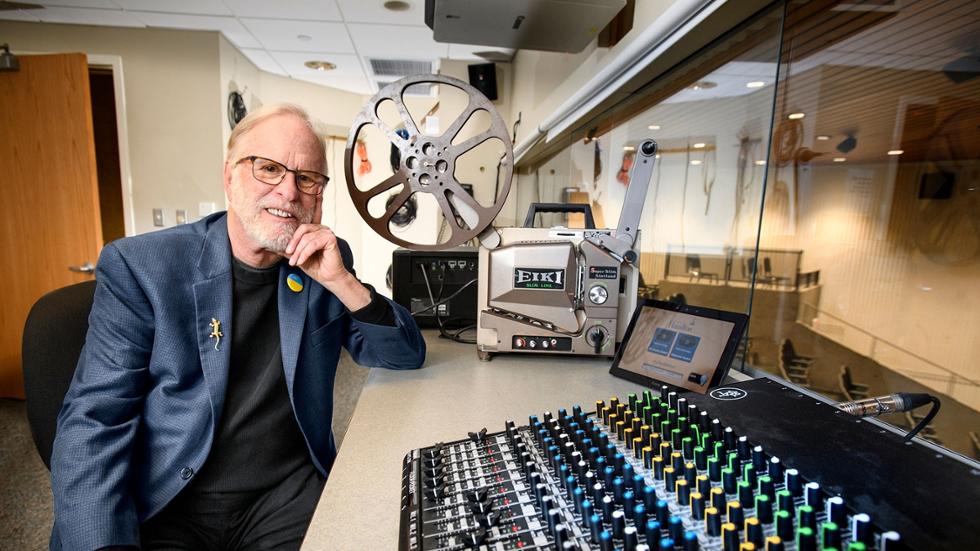

Scott MacDonald is professor of cinema and media studies and director of Hamilton’s .

Posted August 25, 2025